Monday, January 31, 2022

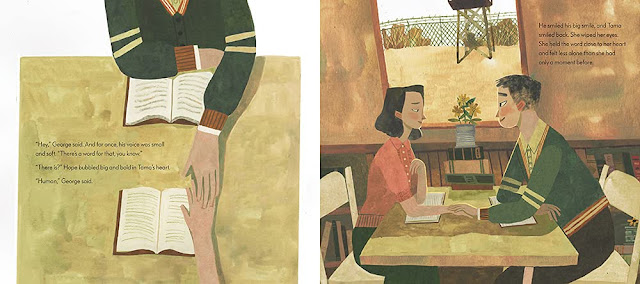

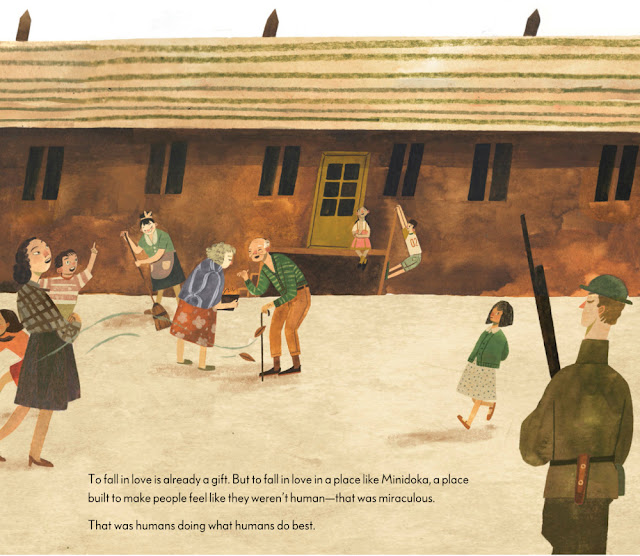

Love in the Library by Maggie Tokuda-Hall, illustrated by Yas Imamura

Monday, February 15, 2021

Mei Ling in China City/Mei Ling en la Ciudad China by Icy Smith, illustrated by Gayle Garner Roski

An interesting story about the real life for one Chinese American girl in 1942.

|

| A 1940s photo of the restaurant owned by Mei Ling's family |

Thursday, September 24, 2020

Displacement written and illustrated by Kiku Hughes

Suddenly, Kiku finds herself in the audience of a violin recital where a young version of her grandmother, Ernestina Teranishi, is performing. Kiku didn't know her grandmother, but she did know that she had been a gifted violinist. Returning to the present, Kiku and her mother head to the hotel, and hear Donald Trump calling for a total shutdown of Muslims entering the US.

Before leaving San Francisco, Kiku displaces again, this time after Executive Order 9066 has been issued and she finds herself in a line of people being watched by armed guards. Again, returning to the present and heading home to Seattle, Kiku realizes how little she knows about her own Japanese culture and history, in part because her grandmother never spoke to her mother about what happened to the Japanese Americans in the camps.

Back in Seattle, Kiku displaces once again, finding herself reduced to being Number 19106, and traveling on the same bus as the Teranishi family, heading to Tanforan Assembly Center, a racetrack where the Japanese Americans are forced to live in horse stalls that still smell of manure. There, Kiku lives with a roommate, Aiko Mifune, right next door to the Teranishi family.

Kiku's first two displacements were for short periods of time, but now she finds herself living in the past for an extended time. This means that Kiku can learn something about her grandmother and great grandparents, but it enables author Kiku Hughes to show what went on behind the barbed wire and armed guards. The overcrowding, the poor quality of the food, the lack of privacy in the latrines and showers are part of daily life there, but so is the tenacious spirit of the Japanese people, who are determined to turn their living conditions into something better. Kiku even finds a love interest.

By the time Kiku is transferred to the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah, she knows she won't be returning to the present anytime soon, and determines to make the best of her situation. Once again, she finds herself living near her grandmother and even her love interest from Tanforan. The whole time she is torn as to whether or not to introduce herself to her grandmother, or merely to continue to observe her from afar. Life in Topaz is a real eye-opener for Kiku. People who had been productive and law-abiding are now incarcerated and deprived of their civil rights. When the government issues a loyalty questionnaire, those who refuse to answer yes on questions 27 and 28, and renounce their Japanese ancestry, face harsh punishment, including Kiku friend Aiko. But after after someone was shot and killed, people really begin to worry about their safety. Does Kiku ever return to the present? Yes, of course, and at a very interesting point in her story. But does her experience in the past change her?Displacement is somewhat autobiographical for author Hughes, who also never knew the grandmother who had been in the internment camps during the war. Sending Kiku back in time enables her to show the personal and community trauma that was inflicted on people who had done nothing wrong. What I found most telling is Kiku's feelings of helplessness and her gradual acceptance of her incarceration. That was scary, given today's world.

I think Hughes really captured Kiku's emotional truth, and through her, readers also know the emotional truth of her grandmother and all the other Japanese people who had been incarcerated for no other reason than their race. Though the word interned is generally used to describe what happened, Hughes chooses to use incarceration, given that people had no freedom and lived surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards, it really did resemble prison-like conditions.

Displacement is one of the best graphic novels I have read about the Japanese American experience in WWII. You might want to pair it with George Takei's They Called Us Enemy.

You can find an interesting and enlightening interview with Kiku Hughes HERE

Monday, July 6, 2020

They Called Us Enemy by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, and Steven Scott, illustrated by Harmony Becker

Monday, December 2, 2019

A Scarf for Keiko by Ann Malaspina, illustrated by Merrilee Liddiard

But Sam hates knitting and he isn't very good at it, unlike Keiko Saito, whom he's know for years and who sits next to him in school and is a great knitter. But whenever she offers to help him, he refuses. In fact, Sam now refuses to have anything to do with Keiko, even after witnessing her being harassed by a teenager as she rode her bike home from school.

But when Sam's mom sends him to the flower shop for some flowers for Shabbat, he sees that Mr. Saito's grocery has been vandalized and Go Back to Japan is written on the closed flower shop. During the Shabbat meal, Sam's dad tells him and him mom that President Roosevelt has decided going to send people of Japanese ancestry away, fearing they might be spies for Japan.

On Monday, Keiko isn't in school, but Sam sees her after school, knitting in front of her house. At home, Sam's mom tells him the Saito have to pack and leave soon, taking only what they can carry and she has volunteered to care for Mrs. Saito's lovely tea set. On the morning after the Saitos have left, Sam finds Keiko's bike in front of his house with a note for him to use it while she's away and a pair of hand knit socks for his brother Mike.

Thinking that Keiko will be cold where she is in the desert, Sam is determined to learn how to knit something to send her: a lovely red scarf to keep her warm.

A Scarf for Keiko is a great story about tolerance and how easy it is to be swayed by friends into turning on good neighbors and friends because they are being portrayed as being un-American simply for being who they are. It also shows how conflicted Sam is about no longer being friends with Keiko, whose family has been such good neighbors with his family, and the way his brother Mike helped Keiko fix her bike, and then not speaking up when he sees injustice all around him. He conflict is increased when his mother reminds the family that her sisters in Poland are in danger because they are Jewish and that Mike is in danger as a soldier.

The simple illustrations add much to the story and are done in a muted palette of blues, browns, greys, and touches of red that give a retro feeling. Faces are a bit exaggerated so that they reflect the wide spectrum of character's emotions - fear, conflict, worry, sadness, hate, kindness, even happiness.

A Scarf for Keiko is a great picture book for older readers who may be old enough to have witnessed acts of intolerance in today's world and are also conflicted about what is happening.

Back matter includes an Author's Note that explains why and how people of Japanese ancestry, including Japanese Americans like Keiko and her family, were put in internment camps by President Roosevelt's Executive Order 9066. I need to mention that there is a typo here, stating the date of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor as December 6, 1941, when in reality it was December 7, 1941. Other than that typo, this is an excellent book to share with young readers.

Teachers and students can find a useful downloadable Activity Guide for this book HERE

This book is recommended for readers age 7+

This book was borrowed from the NYPL

Sunday, August 18, 2019

A Place to Belong by Cynthia Kadohata

Having lost their home, their restaurant, their possessions, even Hanako's cat, the Tachibana family were living in internment camps since 1942, after President Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 9066. They had ended up in Tule Lake in 1943 because Mr. Tachibana had refused to answer yes to one of two loyalty questions on a government questionnaire designed to separate loyal from disloyal Japanese American men. Ultimately, Hanako's parents decided renounced their American citizenship when pressed to do so by the government and the family was repatriated to Japan at the end of the war, a country neither Hanako nor Akira had ever been to before.

Hanako expects Japan to look as beautiful as it had in pictures she had seen, but the reality is a Japan that is as broken and poverty-stricken as she feels. Traveling to her paternal grandparents, tenant farmers living just outside of Hiroshima and struggling to survive, Hanako witnesses soldiers and civilians, dirty, disheveled, often crippled, begging for something to eat, as well as the destruction all around her, blackened trees, buildings and homes turned to rubble, all as a result of the atom bomb that had been dropped there by the Americans.

At her grandparents home, Jiichan (grandfather) and Baachan (grandmother) welcome the family with open arms and unconditional love, despite not even having enough to eat for themselves. Hanako helps out as much as she can working in the fields, but soon finds herself in school, where she is treated like an outsider. Although she can get by speaking Japanese, her reading and writing are almost non-existence, as is her skill using an abacus. Even her long braid is cause for criticism among the other girls.

Hanako is a sensitive, observant, questioning girl, who is growing up too quickly, but is stuck in the past and afraid of the future. One of the first things Jiichan teaches her is that the way to move forward is through kintsukuroi, which is a way of repairing broken pottery using lacquer dusted with gold, so the repaired pottery is even more beautiful than it had originally been. The trauma of having lost everything has caused Hanako to question who she is, where she belongs, and what she now believes in. She may feel like a broken piece of pottery, but Hanako figures life is more complicated than a repaired bowl.

Eventually, however, Hanako's parents decide that they would like to return to America and begin working with an American civil rights lawyer, Wayne Collins, to make that happen. Mr. Collins is putting together a class action suit to help those who were repatriated to Japan after the war to regain their citizenship and return to America. But when her parents petition is refused, the family is forced to make some hard decisions. Yet, through everything that has happened to her family, Hanako finally begins to understand her grandfather's lesson on kinsukuroi, and learns that in life gold can take many forms, and that understanding is just what she needs to be able to move forward with her life.

I won't lie, A Place to Belong is a difficult book to read. Not because of the writing, which is beautifully straightforward. Or the characters, which are drawn so well you feel like you really know them. What makes it difficult is the reality of what happens, and knowing that Hanako's life is broken because of war, because of who she is and what is done to her by her own country - the United States. In addition, descriptions of children and adults begging in the streets, of people starving and disfigured in the aftermath of the atomic bomb, of black markets taking advantage of desperate people offer a disturbing, yet realistic look at post-war Japan even as Hanako tries to piece together just who she is amid the wreckage within and around her.

A Place to Belong is historical fiction based on real events. All men of Japanese ancestry really were required to complete the so-called "loyalty questionnaire" in 1943 and they, along with their families, were sent to Tule Lake Concentration Camp if they were deemed disloyal based on their answers. Tule Lake was a harsh, cruel place where inmates were treated like prisoners and many, like Hanako's family, were deported to Japan after the war.

A Place to Belong should be read by anyone interested in WWII history, however, I think readers will definitely see parallels to much of what is happening in our world today. Be sure to read Kadahata's Afterword for more information about Wayne Collins and the work he did on behalf of wronged Japanese Americans.

You can download a reading guide for A Place to Belong from the publisher, Simon & Schuster, HERE

You might want to pair A Place to Belong with No-No Boy by John Okada. No-No Boy looks at the post-war life of a Japanese American boy who answered no to both of the loyalty questions, but did not give up his citizenship.

This book is recommended for readers age 10+

This book was provided to me by the publisher, Simon & Schuster, with gratitude

|

| View of barracks with Castle Rock in the background, Mar. 20, 1946, Tule Lake concentration camp, California.. (2015, July 17). Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 08:05, August 17, 2019 from https://encyclopedia.densho.org/sources/en-denshopd-i37-00239-1/. |

Thursday, March 14, 2019

Fish for Jimmy: Inspired by One Family's Experience in a Japanese American Internment Camp written and illustrated by Katie Yamasaki

But early in December, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, their father is taken away by three men in the FBI. The family can no longer live in their home and run their Farmer's Market, and Jimmy, Taro and their mother find themselves "forced to live in tiny barracks surrounded by guards." Confused about what is happening, Jimmy refuses to eat the unfamiliar food he is served.

And no matter how much they try to coax him, no one can get Jimmy to eat. Although everyone is worried about him, Jimmy just doesn't understand why his family isn't living in their home near the ocean. Or why they can't eat his mother's good rice and noodles, or the fresh vegetables and fish he loves so much? Soon, Jimmy even stops playing with the other kids.

One night, Taro, worried about Jimmy and feeling responsible for taking care of him in their father's absence, makes a big decision. Taking a borrowed pair of garden shears, he quietly leaves the barrack, find a place in the fence where the guards can't see him and clips a hole he can crawl through.

Finding a mountain stream, Taro waits until he feels a fish hitting against his leg, then quickly grabs fish after fish, wrapping them in his mother's scarf. And in the morning, there is fish for Jimmy, who finally eats to his mother and Taro's relief.

In her end note, author Katie Yamasaki writes that Fish for Jimmy is based on a true story from her family's history. Her great-grandfather was arrested by the FBI just as Taro and Jimmy's father had been, though it was her grandfather's cousin who snuck out of the camp to find fish for his young son. I think that by putting the stories together, Yamasaki is able to highlight the impact that interning innocent people, particularly children, based solely on their ethnicity through Jimmy's depression and his refusal to eat and works to make this a very accessible story for young readers. Sadly, it made me think about all the Jimmys who found themselves in these camps and who were too young to understand what was happening.

The illustrations, done with acrylic paint, vividly capture the emotions each person is feeling. The reader sees Jimmy going from a happy little boy to a depressed child and finally as a smiling kid after having a taste of home again. The danger Taro faced sneaking out to catch the fish is aptly shown in a spread with the barbed wire fence in the foreground and guards with big guns in the background, and behind that, readers can see Taro's searching for the right spot in the fence to cut through. It is a wonderful, dynamic, rather sophisticated image, and Yamasaki the muralist painter is really present in it.

Fish for Jimmy is an excellent choice for introducing the history of the internment of Japanese Americans to young readers and it will definitely resonate with things happening in today's world for them.

This book is recommended for readers age 6+

This book was borrowed from the Bank Street School Library

Saturday, December 15, 2018

Baseball Saved Us by Ken Mochizuki, illustrated by Dom Lee

The story is told in the first person by a young boy in an unnamed internment camp, whose father has decided to make a baseball field in the desert where the camp is located to give people something to do. Not particularly excited about that, the boy recalls that in school before being order to leave his home with his family, he was never picked to play on any sports teams when the other kids were choosing sides because of he was so much shorter and smaller that the other kids.

Everyone pulls together and soon the baseball field is finished, mattress ticking is turned into uniforms, teams are forms and it's time to play ball. Playing on one of these teams is easier for the boy because the other kids were pretty much the same size, but it didn't really help his game much.

During one game, he notices that the soldier in the guardhouse is watching him. Taking a few practice swings, the boy puts all his resentment and anger into his next swing, and sure enough, he made his first home run.

After the war, when the Japanese Americans who were held in internment camps are finally released and allowed to return home, the narrator finds himself once again alone at school. But when baseball season comes around, this time he proves himself a pretty good player, earning the nickname "Shorty." At a game, when it's his turn at bat, Shorty can hear the crowd screaming and calling him names. Thinking about the guard in the watchtower and how he took his anger out on the bat, Shorty once again calls on the feeling as the crowd jeers him and putting it all into his swing, sends the ball over the fence, saving the day for his team:

Of course, this isn't really a story about baseball, but it is one about racism and offers a constructive way of dealing with feelings of anger and resentment, while gaining a sense of dignity and self-respect. It's interesting that the narrator has no name until the boys at school after the war give him a nickname. It's as though he had lost his identity until he began believing in himself.

Baseball Saved Us is not just a good story with an important message. It is also a good book for introducing the whole history of Japanese American internment to young readers without overwhelming them. In the course of the story, Shorty says that he was taken out of school by his parents one day, and that his family soon found themselves living in horse stalls before moving to the camp in the desert, where they were subjected to dust storms and sand everywhere. He also points out that people were forced to lived in barracks without walls, to wait in line to eat or to use the bathroom, where there was no privacy. His older brother ate with his friends, but soon was refusing to do what his parents requested - a big problem with older kids in the internment camps. This offers a wonderful opportunity to expand on how people perceived to be an enemy of the United States can be treated so badly.

This is a book that many kids will find resonates in today's world even though it was written 25 years ago about the racism and prejudice that was so prevalent in WWII more than 70 years ago.

You can find a useful educator's guide courtesy of the publisher Lee & Low HERE

You can read Jason Low's thoughts about diversity and the 25th anniversary of Baseball Saved Us HERE

This book is recommended for readers age 7+

This book was borrowed from the NYPL

Thursday, June 7, 2018

Write to Me: Letters from Japanese American Children to the Librarian They Left Behind by Cynthia Grady, illustrated by Amiko Hirao

Write to Me is the story of one San Diego librarian, Clara Breed, who saw the injustice of incarcerating innocent people and whole families and tried to make it somewhat bearable for her young library patrons. Grady begins with the sad moment when young Katherine Tasaki has to return her books and relinquish her library card. Later, seeing the children she knew from the library off at the train station, Miss Breed gave out books and stamped postcards for the kids to write and let her know how and where they are and if they needed anything.

Soon, the postcards Miss Breed had give out began to arrive at the library from [Santa Anita Racetrack] Arcadia, California. She began writing the kids, sending them boxes of books and more postcards. The one time she visited Santa Anita, she brought even more books. After seeing the kinds of circumstances her young friends were being subjected to and the enjoyment the books she sent gave them, Miss Breed began writing letters and magazine articles asking for libraries to be opened in the internment camps for the kids to have easier access to reading.

Miss Breed continued to correspond with the kids she knew even after they were moved to the Poston Internment Camp in Poston, Arizona, in the middle of the desert. She also continued sending books, as well seeds, thread, soap, and crafts materials. Learning about the harsh desert conditions they lived with everyday, Miss Breed continued to write letters and magazine articles, hoping to make the country aware of how its citizens were being treated.

Write to Me is a picture book for older readers who are just beginning to learn about this period of American history and while it focused on Miss Breed's actions more than on the actual treatment of the Japanese American families she tried to help or the pervasive racism towards them, it does show young readers that one person can really make a difference in the lives of others. I think that's a message that will certainly resonate for them in today's world.

Interestingly, the focus of each of Amiko Hirao's gently muted color pencil illustrations is reflected in the postcard excerpts sent by the children that are found on almost every page.

There is extensive back matter, including an Author's Note, a recounting of Notable Dates in Clara Breed's Life, Selected History of Japanese People in the United States, a Selected Bibliography, and suggestions for Further Reading. The front and back end papers contain relevant captioned photographs.

Though it is for a somewhat older child, with scaffolding teachers might want to pair this with I Am An American by Jerry Stanly, for a more rounded picture of Japanese American internment camps.

The Japanese American National Museum has an online collection of letters written to Clara Breed from her young patrons incarcerated in internment camps, including Katherine Tasaki. You can read them HERE

One of the magazines Clara Breed wrote articles for was the Horn Book Magazine and you can read one of her articles "American with the Wrong Ancestors" published July 7, 1943 HERE

This book is recommended for readers age 6+

This book was purchased for my personal library

Clara Breed wrote another article in Jan/Feb 1945 issue of the Horn Book Magazine, which is not online but I found it in the library. The article is "Books That Build Better Racial Attitudes" and while it is really dated, I was curious to see what she recommended. One of the books is called The Moved-Outers by Florence C. Means, about the internment of a Japanese American family, and may very possibly be the first book about it. It was also a 1946 Newbery Honor book. I actually read it when I was researching my dissertation, but ultimately didn't use it, except as an example of patriotic propaganda. I'm definitely going to have to reread it one of these days.

Saturday, September 2, 2017

Fred Korematsu Speaks Up by Laura Atkins and Stan Yogi, illustrated by Yutaka Houlette

This book is recommended for readers age 9+

This book was bought for my personal libraty

Wednesday, January 11, 2017

Four-Four-Two by Dean Hughes

Now, in April 1943, Yuki, his mother, younger brother Mick, and sisters Kay and May have all been living in the Central Utah Relocation Center, also known as Topaz. In fact, all west coast Japanese peoples, regardless of whether they were Nisei, born in the United States and whose parents were from Japan, or Issei, first generation Japanese immigrants, had been relocated to various internment camps around the country, as per Executive Order 9066 signed by President Roosevelt.

The United States mow needs more soldiers and are letting Japanese men enlist, as long as they swear allegiance to this country. Having just turned 18 years old, Yuki and his best friend Shigeo 'Shig' Omura have both decided to enlist, and despite the fact that the country he is going to defend is still holding his father prisoner. Yuki is determined to prove his loyalty to his country.

As part of the all Japanese 442nd Regimental Combat Team, Yuki and Shig find basic training hard and tough, but they are determined to prove themselves. Added to that, Japanese recruits find they are still facing the same racist attitudes from others in and around Camp Shelby, Mississippi, even though they are fighting for the same country. But then, basic training gave way to endless war games and Yuki thought they would never get a chance to fight. But, finally, in March 1944, the Four-Four-Two received their orders to ship out to Italy.

Although they had been anxious to get to the front, Yuki and Shig aren't really emotionally prepared for what they find in combat. Death and destruction surrounds them, friends are lost, and Yuki discovers that the enemy is now just a kid like he and Shig. He gets a small break from the fighting because of a very serious case of trench foot exacerbated by having to wear combat boots. But for Yuki, the hardest part of battle was still to come before he could find his way home.

I have to honest and say I don't care much for books where most of the action takes place on the battlefield, I am generally much more interested in the home front then the front lines. That said, I found Four-Four-Two to be a very interesting novel. Most books about Japanese internment during WWII are focused on the families living in those camps. Even when the young men enlist and go to war, the story stayed focused on the family at home.

But by focusing on two young Japanese American men who enlist in the army, author Dean Hughes is able to show that even though they were fighting on the same side as other Americans, they were still segregated into their own regiment, the 442nd. Men like Yuki and Shig had to constantly deal with racial prejudice both in the army and away from it. One telling example is the barber who refuses to cut "Jap hair" despite Yuki's uniform and the two medals he wore on the (a purple heart and a Silver Star for gallantry in action).

Hughes begins Four-Four-Two with a Preface that explains how some Americans saw German, Italian and Japanese immigrants at the start of the war, and why. Japanese immigrants were not allowed to become citizens, and Hughes goes on the give background into the treatment of Issei as 'enemy aliens', and includes details about the exemplary wartime performance of their sons who joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Also included is a breakdown of military units for people like me, who can never keep them straight.

This is a book that should appeal to anyone interested in WWII, Japanese American history and I think they will find that parts of it unfortunately still resonates in today's world.

This book is recommended for readers age 13+

This book was an EARC received from Edelweiss/Above the Treeline

Monday, February 15, 2016

Paper Wishes by Lois Sepahban

At school, Manami is told it is her last day, the last day for all the Japanese students. Instead of school, Manami, her mother, father and grandfather must register in order to be sent away to an unknown place taking only what they can carry. Grandfather has made arrangement for Yujiin to be picked up by their minister, since not pets are allowed to go with them. Unable to leave him behind, Manami hides the little dog inside her coat and no one notices until they are far from home. A soldier puts Yujiin in a crate and he is left behind.

Traumatized by all that she has just experienced, unable to bear the pain of losing Yujiin and the hurt it has caused her grandfather, Yujiin finds herself unable to speak. Eventually, the Tanaka's arrive at a half built Manzanar internment camp, where they must share one small room with a women and her many children. Mr. Tanaka joins the building team responsible for constructing new barracks as more and more Japanese family arrive. Mrs. Tanaka takes a job working in the kitchens. Both parents are thankful that their older children, Ron and Keiko, are still away at college, but Manami writes and asks them to come to Manzanar. The letters get lost, but soon Ron arrives.

Eventually, a school opens and Ron takes a teaching job there, which makes Manami very happy. She begins to believe that Ron got her letter to him because it was caught by the wind which blows all the time. Still unable to find her voice, and living with unbearable guilt over what happened to their dog, Manami begins to think she sees Yujiin looking for her around the camp. Realizing he isn't really there, Manami begins to write letters to Yujiin to come to her in the camp and releases them into the wind.

Anyone who has ever lost a pet tragically will understand Manami's heartbreak - but she is dealing not just her own feelings, but also having to see her grandfather's heartbreak as well. And this heartbreak is compounded by the sudden loss of everything she ever knew, and removal to a hostile, unfriendly crowded place surrounded by barbed wire and guards with guns, and all because of her Japanese heritage. I can't even imagine how a 10 year old could cope with all that even with a strong, understanding family like the Tanakas.

Lois Sepahban has drawn realistic, believable characters, who even under these terrible circumstances show a level of courage, dignity, and resiliency that is admirable, and who despite the worst circumstances, manage to thrive, like Mrs. Tanaka's garden. It's a short novel, told entirely on the first person from Manani's point of view, which accounts for the lack of many things that went on around her but she which has no knowledge of. In fact, Paper Wishes almost feels like a novella, and yet, the writing is so expressive, so emotional, it almost reads like poetry.

Paper Wishes is Sepahban's debut middle grade novel, though she has a number of nonfiction works to her credit. It is an excellent work of historical fiction, though it is not a history book about Manzanar, but rather about the traumatizing effects displacement, discrimination and loss have on one young girl and her family. And it is a novel that will certainly resonate with today's readers.

Be sure to read the Author's Note at the end of the novel.

You find more information about the Japanese people from Bainbridge Island who were deported to internment camps HERE

This book is recommended for readers age 9+

This book was an EARC received from NetGalley

Sunday, December 14, 2014

Hunt for the Bamboo Rat by Graham Salsibury

All that changes when Zenji's JROTC commanding officer Colonel Blake shows up at his house one day. He wants Zenji to be interviewed and tested, but for what? To travel to the Philippines to translate some documents from Japanese to English.

But when Zenji arrives in Manila, he is instructed to stay at the Momo, a hotel where Japanese businessmen like staying, to befriend them and keep his ears and eyes open. He is given the key to a mail box that he is required to check twice a day to be use for leaving and receiving information and instructions. Zenji is also given a contact person, Colonel Jake Olsten, head of G2, the Military Intelligence Service, and even a code name - the Bamboo Rat.

In December 1941, the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor and the war in the Pacific begins. It isn't long before the Americans are forced to withdraw from Manila. Zenji chooses to remain, giving his seat on the last plane out to another Japanese American with a family. Not long after that, he is taken prisoner by the Japanese, who torture and threaten him trying to make him admit he is the Bamboo Rat, and considering him a traitor to his county - Japan.

Eventually, the Japanese give up and Zenji is sent to work as a houseboy/translator for the more humane Colonel Fujimoto. Fujimoto seems to forget that Zenji is a prisoner of war, and begins to trust him more and more.

By late 1944, it's clear the Japanese are losing the war in the Pacific. They decide to evacuate Manila and go to Baguio. Even though food is in short supply, Zenji starts to put some aside for the day he may be able to escape into the jungle and wait for the war to end.

But of course, the best laid plans don't always work out the way we would like them to and that is true for Zenji. Will he ever make it back to Honolulu and his family?

WOW! Graham Salisbury can really write an action-packed, exciting and suspenseful novel. Salisbury was born and raised in Hawaii, so he gives his books a sense of place that pulsating with life. Not many authors explore the Japanese American in Hawaii experience during World War II and not many people realize that they were never, for the most part, interned in camps the way the Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians on the west coast of the US and Canada were. And although Hawaii was only an American territory until it became a state in 1959, if you were born there, you had American citizenship, just like Zenji continuously tells his Japanese captors throughout Hunt for the Bamboo Rat.

At first, I thought Zenji was too gentle, too innocent and too trusting for the kind of work he was recruited to do, which amounted to the dangerous job of spying. But he proved to be a strong, tough character even while he retained those his aspects of his nature. Ironically, part of his survival as a spy and a POW is based in what his Japanese Buddhist priests had taught him before the war.

One of the nice elements that Salisbury included are the little poems Zenji's mother wrote. Devising a form of her own, and written in Kanji, it is her way of expressing her feelings. They are scattered throughout the book. Zenji receives one in the mail just before the bombing of Pearl Harbor and keeps it with him as long as he can, deriving comfort from it.

Like the first novel I read by Salisbury, Eyes of the Emperor, one kept me reading straight through until I finished it. It is the fourth novel in his Prisoners of the Empire series, and it is a well-crafted, well-researched story, but it is a stand alone novel. Zenji's story is based on the real wartime experiences of Richard Motoso Sakakida.

True to form, Salisbury brings in a lot of history, along with real people and events, but be careful, fact and fiction are seamlessly woven together. He also includes the tension between the Filipino people and the Japanese after the Philippines are occupied by the Japanese and the cruel treatment of the Filipino people. And included is the tension between Chinese and Japanese in Hawaii because of the Nanjing massacre of Chinese civilians in 1937/38.

All of this gives Hunt for the Bamboo Rat a feeling of authenticity. There is some violence and reading the about Zenji's torture isn't easy, so it may not appeal to the faint at heart.

Hunt for the Bamboo Rat is historical fiction that will definetely appeal to readers, whether or not they particularly enjoy WWII fiction. And be sure to look at the Author's Note, the Glossary and additional Resources at the end of the novel.

This book is recommended for readers age 12+

This book was purchased for my personal library

Monday, June 9, 2014

Gaijin: American Prisoner of War written and illustrated by Matt Faulkner

Finally, Koji's mom receives a letter saying that he is to be sent to a "relocation camp" which is nothing more than the Alameda Downs, a former racetrack. His mother decides to go with him, but because she is white, not Japanese, she and the camp commander become friends. Koji, who is called Gaijin (outsider) by the other Japanese boys finds himself getting bullied by them. After getting caught fighting, an elderly old family friend man, Yoshi Asai, takes Koji under his wing. But after the two create a Victory Garden, the bullies go after it night after night.

Koji finds himself getting more and more angry as the days go by, at the government for putting them in horse stables and then treating them like they are all criminals; at the bullies for making him feel like he doesn't belong anywhere. Pretty soon a rift develops between Koji and his mom, fueled by the bullies repeatedly calling her the camp floozy.

The bullies set up all kinds of dangerous tasks for Koji to do with the promise of belonging as his reward. As the tasks get riskier, Koji faces the possibility of being sent to a very unpleasant correction facility alone. Is his desire to belong or his anger so great that his is willing to risk that fate? Or can the gentle elderly Mr. Yoshi Asai help keep Koji from getting into more trouble?

Gaijin: American Prisoner of War is based on a true story from author/illustrator Matt Faulkner's family, as he explains at the end of the story, making it personal and affecting. Using the graphic novel format, allows the reader to see the anger, confusion, fear, all the understandable feelings of a young man forced to live the way the Miyamoto's were, and being treated like an enemy alien because of his race, not his citizenship.

The illustrations are done using watercolor and gouache in rich vibrant colors very reminiscent of the early 1940s. Gouache is the perfect medium for this graphic novel, with its large bold energetic images, sometimes only one to a pages, other times as many as five. Much of the story comes through the illustrations, with little text but together they really capture every humiliating element of the internment of the Japanese in WWII.

The more I read graphic novels, the more I appreciate them. When they are done well, as Gaijin is, they can be a way of introducing difficult topics to young readers and may serve as a way to interest reluctant readers.

Another excellent book about this still not widely known about part of American history.

This book is recommended for readers age 9+

This book was bought for my personal library

Tuesday, January 7, 2014

Dust of Eden by Mariko Nagai

Mina Masako Tagawa, 12, was living a pretty contented life in Seattle, Washington in 1941 with her parents, older brother Nick and grandfather. But when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Mina soon discovers that, with the exception of her best friend Jamie, old friends are now new enemies. Soon her father is taken into custody, merchants refuse to sell food ro them, kids in school hiss the words Jap and go home at Masako.

In February 1942, President Roosevelt signs Executive Order 9066 and before they know it, the Tagawa family is temporarily relocated to a place called Camp Puyallup Assembly Center, euphemistically called Camp Harmony. A former fair site, the Tagawas are placed in a former horse stall, and given bags to fill with hay to sleep on.

Living conditions are terrible, but in August 1942 the family is moved to the Minidoka Relocation Center in Hunt, Idaho. Eventually a makeshift school is set up that Masako attends. Nick begins to not come home before curfew and is angry all the time, and mother gets a job washing dishes. Eventually, Masako's father returns, now a broken man. Grandpa, however, begins to cultivate roses in the dusty soil.

The Tagawas, like most of the Japanese Americans, were convinced that they would soon be allowed to return to their homes, but as 1942 became 1943, it became clear that was not going to happen. Masako is resentful that they are treated like enemy instead of citizens, but when the US Army begins to accept some of the detained men, her brother wants to join up, against his father's wishes, to prove he is an American.

By 1945, Nick is still fighting in Europe, Grandpa has actually successfully managed to coax roses to grow and many families have started to leave the camp and return home. The Tagawa family has gone through many changes in the years of detainment. Can they really return to the life they once knew in Seattle after such an ordeal?

Dust of Eden is written in free verse, with the exception of the letters exchanged between Nick and his sister. Everything the family experiences is told in the first person in the voice of Masako. This was an interesting, compelling novel, though I found myself annoyed at Masako much of the time. In most stories about Japanese Internment, the main character feels much of the same things that Masako does, but at some point they take charge of their lives even under these oppressive circumstances. But she never does that, and her passivity irked me. Her grandfather was a master grower of roses and she could have at least learned what he had to offer. He was the only one who made an effort to improve their dreadful life.

I thought Nick would have been a more interesting character to read about. Where did he go all those times he was breaking curfew? With whom did he hang out? What was army life like for him as a Japanese American?

I would still recommend this novel, since it does give us another perspective on the treatment of Japanese Americans in WW2 by our government and citizens, not our shiniest moment. It would pair nicely with Imprisoned: the betrayal of Japanese Americans during World War II by Martin W. Sandler, which was based on interviews of people interned at around Masako's age.

This book is recommended for readers age 8+

This book was an EARC received from NetGalley

Dust of Eden will be available on March 1, 1014

You can learn more about Minidoka Relocation Center HERE

NB: The cover photograph was taken by Dorothea Lange. Lange was a talented photographer hired by the War Location Authority to photograph the relocation of Japanese Americans in WW2. Lange's photographs were so critical of the government and so sympathetic to the Japanese Americans that they were censored by the government and not seen for many years. You can find some examples of her work at the Library of Congress online exhibit "Women Come to the Front"

Monday, August 26, 2013

Imprisoned: The Betrayal of Japanese Americans during World War II by Martin W. Sandler

But, as Sandler points out, fear and mistrust of Japanese immigrants to the US didn't begin with World War II. And so, we are given a short history about the arrival of the Japanese; their willingness to take any kind of work when they first arrived here; how they saved their money and how they were eventually able to afford their piece of the American Dream.

But they looked different, their language was different, their religion and culture were different and so they faced anti-Japanese signs and sentiments all over the West Coast. As more Japanese arrived, laws were passed preventing Japanese immigrants from owning law, then congress passed the Immigration Act, which banned Japanese immigration to the US altogether. And of course, according to The Naturalization Act of 1790, citizenship was already out of the question for any non-white not born on American soil. Yet, despite all of these obstacles, Sandler points out, the Japanese still managed to thrive in this country.

That was until December 7, 1941, when the Japan attacked the United States in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Once again, fear and mistrust reared up. And, despite the fact that there was no indication that the Japanese and their Americans born children were the least bit sympathetic to or in cahoots with Japan, it didn't take long for the hate and suspicion mongers to convince the President of the United States to sign Executive Order 9066 placing them in internment camps.

In this relatively short (176 pages), well researched, well written book, Sandler gives us tells the story of life in the internments camps through personal accounts and interviews never before published, all supplemented with a abundance of photographs, providing a more in-depth look at what went on before, during and after the war.

It was a little difficult reading this book because it was from Net Galley and I downloaded it to my Kindle App and the photos weren't where they should have been and the wonderful personal accounts that are included were also kind of helter-skelter so I am very anxious to see and reread the actual book when it comes out on August 27, 2013.

Despite my difficulty reading Imprisoned, I would still highly recommend it to anyone interested in WW2 home front history. A nice companion book, which Sandler also mentions is Citizen 13660 by Miné Okubo, which I review back in 2011.

The story of internment of Japanese and Japanese Americans didn't end with WW2. Given $25 and a ticket home, Sandler goes on to briefly cover how the internees returned to their homes to find everything gone, how they worked hard to get back on their feet yet again,despite yet more obstacles, and finally, their fight for reparations in the 1970s and 1980s.

There is copious back matter including places to visit, websites with additional information and a nice in-depth index (one of my favorite back matter elements that often is not as well done as this one).

This book is recommended for readers age 10+

This book was an E-ARC from Net Galley

Monday, May 20, 2013

Barbed Wire Baseball by Marissa Moss, illustrated by Yuko Shimizu

By now married with two teenage sons, Zeni and his family were forced to move to an internment camp just because they were of Japanese descent. Located on the Gila River Indian Reservation, it was hot and dry desert with too many people crowded into barrack after barrack, each containing row upon row of cots.

While families tried to make a home out of their allotted space, putting up curtains and decorating with all kinds of personal mementos, Zeni still dreamed about baseball and decided he was going to play - right in the desert!

And so he picked a spot and began to clear the grass and rocks, hard work in the desert heat. Yet before he knew it, others joined in to help, including his own sons. Using his ingenuity, his power of persuasion and any other means possible, little by little, Zeni and his helpers began to turn the desert into a baseball field, right down to bleaches for people to sit and watch games. And while the men worked on building a field, the women sewed uniforms out of potato sacks. Lastly, equipment was purchased with funds collected from among the detainees.

Barbed Wire Baseball is an excellent introduction to both Japanese American baseball and the internment of Japanese American in World War II. Marissa Moss gives the same attention to detail in her text that Zeni gave to creating his baseball field. And the beautiful illustrations by Yuko Shimizu bring the whole story together. This is the first children's book that Shimizu has illustrated and for it, she used a Japanese calligraphy brush and ink, than scanned and colored the illustrations with Photoshop, so that the colors give a real sense of the time.

At the end of Barbed Wire Baseball, there is an Afterword about Kenichi Zenimura life, as well as an Author's Note and an Artist's Note, which you may not want to miss reading. Moss has also included an useful Bibliography for further exploration of Japanese American baseball.

I had never heard of Kenochi Zenimura before, probably because I'm not much of a baseball person, but I really was impressed with his perseverance and dedication to creating a place where he and his fellow detainees could enjoy playing or watching baseball in an otherwise desolate place and that would give them all a sense of accomplishment and community. And having lived in Phoenix, AZ for 4 years and being somewhat familiar with the desert around it, I really understood what an accomplishment it was.

|

| 1927: Zenimura standing between Lou Gehrig and Babe Ruth (also depicted on Page 10 of Barbed Wire Baseball) |

This book is a Picture Book for Older Readers and is recommeded for readers age 7+

This book was borrowed from the NYPL

Nonfiction Monday is hosted this week by Perogies & Gyoza